We leave Flensburg in the morning after topping up with fuel. The tank is still half full, and it is the first top up since we started. Most of it is because we were required to motor through the Kiel Canal, so we haven’t been doing too badly. So far this season, there has been a lot of wind, and we have been making the most of it.

We arrive at the Sønderborg marina on the south side of the town and tie up. It’s a box berth, but we are getting fairly experienced in box berths now, and we glide in gracefully and don’t even miss lassoing the poles on the way in or bump the bow against the pontoon.

“We’ll have to get used to calling everything a ‘-borg’ now that we are in Denmark, rather than a ‘-burg’ as we do in Germany, or a ‘-burgh’ as we do in Scotland”, says the First Mate.

“Not only that, I’ll have to look out how to do all these ‘ø’s, ‘å’s, ‘ö’s and ‘ä’s on my keyboard”, I respond. “Why can’t you Europeans just keep it simple? Twenty-six letters without all this fancy stuff on top are quite enough.”

We cycle into town and check out the shops. The prices are eye-watering.

“I’m glad that we did the ‘big shop’ in Flensburg”, says the First Mate. “At least we have enough to keep us going for the meantime.”

I shudder. My shoulders still haven’t resumed their normal shape.

“Look at all these umbrellas hanging up in the street”, says the First Mate. “I wonder what they signify?”

“Shoes in Flensburg, umbrellas in Sønderborg”, I say. “Do you notice a pattern here? It’ll be underpants in the next town.”

“Don’t be silly”, she says.

The next day, the water has risen again due to a wind change. We can hardly climb back into the boat from the pontoon which is fixed and not floating.

“I know”, says the First Mate. “We can use those little folding steps that we bought in Hoorn. I knew they would come in useful some time.”

They work brilliantly.

The night air chills our bones, and we wrap our cloaks tighter around us and try to snatch what sleep we can. All the way down the hillside are fires, the orange flames leaping skywards as the soldiers throw on more logs. On the hill opposite are the fires of the enemy. I recall playing as a child on the ground that is now under their control. But it won’t be for long. Tomorrow we will show them, and drive them from the land that is rightfully ours, all the way back to the Danevirke.

“We should never have withdrawn from the Danevirke”, says my friend Johan, his face lit by the flickering flames. “It is the border of our country and a symbol of our nation. Abandoning it seems like a dereliction of duty.”

“The swamps at each end of it had frozen”, I say. “The enemy could have ignored the fortifications and just marched around the ends of it. We would have been outflanked. Now try and get some sleep.”

We are awoken in the middle of the night by the dull thunder of the enemy cannon. Seconds later, the balls strike the wooden palisades of our redoubts, destroying them in showers of splinters. Grenades fly through the air behind our lines and explode in deafening claps. The enemy have launched their attack. We leap to our feet, out bodies still cold, tired and exhausted. The gun-smoke irritates our eyes, making it difficult for us to see what is happening. Behind us, the Dybbol Mill is hit and bursts into flames, lighting up the sky like a portent of doom.

In the morning, the Prussians charge our positions. Our men put up a stubborn fight and manage to beat them off. Heroes, every one of them. Our warship, the Rolf Krake, bombards the enemy positions from the bay. The Prussians have no warships and can do nothing about her. Things seem to be going well after all.

But slowly the tide turns. The enemy outnumber us and have modern rifles that they can reload lying down, while we need to stand up and are easy targets. They mount charge after charge, and eventually break through and capture one of our redoubts. And another. And another. Our men lie dead and dying around us. I look for Johan, but he is nowhere to be seen.

We fall back to cross the bridge over the Alsund to Sönderborg. Defeat is written in the faces of the exhausted and dirty soldiers and the civilians that trudge along the road through the mud and snow. We have lost the battle and the war. What will happen now?

One of the stragglers, a young girl, is struggling with a baby in one arm and a bag of her possessions. I put my arm around her to stop her from falling …

“Hey, what do you think you are doing?”, a familiar voice says. “We’re in public, you know!”

It’s the First Mate, of course.

“I was just giving you a hygge”, I say.

We are at the Dybbol Mill on the hill overlooking Sønderborg, the site of the last battle of the Second Schleswig War in 1864, in which the Danes were defeated by the Prussian Army. I am imagining what it might have been like for a Danish soldier during the battle. It has particular resonance with the Danish psyche as it was the battle that lost them the southern part of Jutland to the Germans for more than 50 years. To make matters worse, the Danevirke, a line of fortifications built in AD 650 as a defence against the Saxons and later the Franks, and nowadays the symbol of their national pride, had been within that lost territory, a situation that continues to this day even though the northern part of Schleswig has been returned to them.

We cycle back into town to the museum at Sønderborg Castle. The castle was built around 1200 as a royal palace, but was later taken over by the dukes who ruled Southern Jutland (Sønderjylland) stretching from the River Kongea in the north to the River Eider in the south.

The focus of the museum is on the archaeology and history of the region, particularly the tussles between Germany and Denmark over its sovereignty. Woodrow Wilson’s principle of a ‘people’s right to self-determination’ and the resulting referenda at the end of WW1 to settle the question are described in detail. While it was probably the fairest solution, it has still left national minorities on both sides of the modern day border.

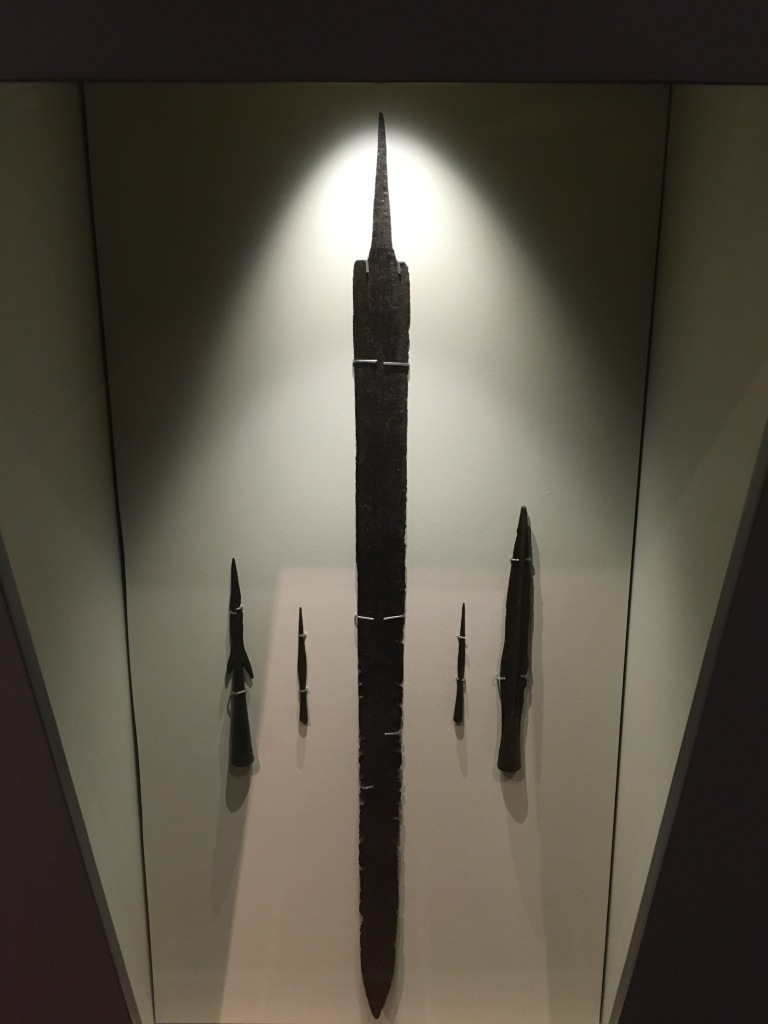

The point is made several times that archaeology is more than just a science – it is also a tool to establish ownership of territory as part of a nation. In the 19th century, many of the finds were examined minutely to see if they were more ‘Danish’ or more ‘German’. Nowadays, helped by membership of the EU, there seems to be more cooperation between the two sides, and archaeologists focus on working together to further the science rather than ownership of a particular piece of land.

We leave the marina at 0900 the next morning and join the queue waiting for the Christian X bridge to open at 0938.

“I wonder why they chose 38 minutes past the hour to open the bridge”, muses the First Mate. “Couldn’t they have made it a round 40 minutes?”

Whatever the reason, the bridge opens punctually at 0938 and we follow the flotilla of other boats through to the Alsund, the stretch of water between South Jutland and the island of Als. The wind is from the north-west, and is a gentle breeze, just enough to allow us to sail majestically along the sound.

We arrive in Dyvig, a small inlet where we have decided to stay the night. Entrance into the small bay at the end is through a narrow buoyed channel about 15 m wide, which we need to negotiate carefully. We drop anchor in 5 m of water on the northern side of the bay where a few other boats are also anchored, and spend the rest of the day relaxing in the warm sunshine.

The next morning I awake to the sight of dappled light playing on the cabin roof reflected through the small side window. I make a cup of tea for myself and go and sit on deck. It is warm and sunny. The water is like a mirror, only the occasional zephyr of wind rippling it momentarily before it returns to its stillness. The other boats drift lazily at anchor, trees lean out over the water, the reflections of both almost perfect images of the real thing. All is quiet.

Except that it is not. As I relax I start to hear sounds that I am not normally aware of, sounds that my brain normally filters out because they are of no use to me in my daily life. Small birds chirrup. Wood pigeons coo in the trees along the water’s edge. A lone seagull mews as it flies overhead. Swans honk on the shingle spit protruding out into the water. A crow calls raucously, then flaps off into the distance. A fish breaks the surface, spreading ever-widening ripples. A cormorant takes to the air, its wing tips beating a rhythmic sound on the surface as it struggles to gain height. A heron stalks primly next to the bank of rushes, from time to time plunging its bill into the water like a stiletto and withdrawing it with a wriggling fish.

I focus still further, and begin to hear a gentle thrum of sound deeper down – the hum of bees, the chirp of insect legs, the rustling of leaves – almost like virtual particles winking in and out of existence, so low that I wonder if I am imagining it. But it is there.

I close my eyes and allow my mind to drift where it wants. Time stops. I am floating, detached from, and yet part of, the natural world around me.

There is a loud splash. Someone from one of the other boats has dived into the water. The world of humans once again asserts its dominance, and my reverie is shattered. It’s time for breakfast.

We weigh anchor at 1000 and set off for Faaborg. There is absolutely no wind, and we need to motor for the first couple of hours. The First Mate goes down below for a nap.

“You know”, says a familiar voice. “I overheard you talking last night about your visits to Dybbol Mill and the museum, and what makes a nation. So I thought I would do a bit of reading on the web.”

It’s Spencer. If you remember from last year, he found a way of linking his web into the Worldwide Wide Web and has become very knowledgeable on a lot of things.

“But I really wonder if the nation state will continue much longer”, he continues. “Its’s only a relatively new concept in the history of human affairs, and already there are a lot of things wrong with it.”

“Like what?”, I ask.

“Well, a nation is supposed to be a grouping of ethnically similar people with a common language, culture, history and territory”, he says. “Most modern nations are anything but that. Take many countries in Africa as examples – most were created on a map by Europeans with no regard for tribal differences and shared languages, and borders often just represented arrangements made between the European colonisers on their areas of influence. Most of the war in the last 100 years or so have been over territory and resources and who owns them. Even here in Denmark, the way that Schleswig was divided between ethnic Germans and Danes still causes unease.”

“I know the nation state concept is not perfect”, I say defensively. “But it is the best we have, and it works. Sort of.”

“Possibly”, says Spencer. “But the forces of the 21st century are causing it to creak at the seams. Globalisation and the internet, for example, are making a mockery of national borders. Some big companies have budgets greater than many countries and others already do things that governments used to do, such as surveillance and mapping. The wealthy are able to escape national restrictions, and governments have lost control over the flows of money that may be generated in their own countries. Where is the nation state in all of this? What we really need is a supranational form of government that national governments are subject to.”

“I am not sure that a world government would gain much traction”, I say.

A tall ship is approaching us, and I break off the conversation to alter course slightly to avoid a collision.

“Look at the disaster unfolding in Afghanistan”, Spencer continues after it has passed. “Twenty years the western countries have tried to build a nation there, and it collapses within weeks after they withdraw. Not exactly a success story. Many in the Muslim world have lost faith in the western concept of a nation state as a form of governance, and want to restore the glories of their past empires, based on their religion. Empires, after all, were the main form of governance for much of human history.”

“But they all fell in the end”, I say. “Most sowed the seeds of their own destruction by overreaching themselves so that they couldn’t afford the costs of maintaining them. Look at the Roman and British Empires, for example.”

“True, but some did achieve a lot while they lasted”, he says. “The Ottoman Empire lasted 700 years and generated amazing prosperity and cultural achievement before it finally declined. Look, I am not saying that more empires are the solution – just that we need different forms of government than the nation state to solve the problems of climate change, globalisation, big data, and all the rest of it. They need to operate at the level of global economic flows so they can be controlled, not underneath it.”

We are approaching Faaborg, and I need to concentrate on entering the harbour. We find a place on the inner pier and tie up. I look for Spencer to continue the conversation, but there is no sign of him.

We have lunch and go to explore the town. Faaborg is an old port, dating to before the 1200s. It became prosperous as a trading centre, trading as far afield as England and the Mediterranean. Nowadays its quaint houses and streets make it a popular tourist attraction.

Just as we are thinking of retiring for the night we hear shouts outside, the sound of an engine, and some bumping of wood against wood.

“I think that we have some new neighbours”, says the First Mate.

I go out to see what is going on. Sure enough, a boat has arrived, and is trying to manoeuvre itself alongside the pier behind us. The darkness is making it difficult. I go and help.

“We are sailing around the archipelago and stopping at different harbours to raise awareness about pollution of our seas”, says the woman, as she throws a rope to me. “It is still legal to dump construction rubble in the seas, and many companies are doing it. Some of it contains toxic material, which is permitted below a certain level, but no-one checks, and many companies are dumping material that is above the limit. It’s killing off sea life. By the way, my name is Vibeke.”

In the morning, I chat to the skipper of the boat.

“Vibeke is a politician”, he says. “She is really concerned about the environment. We are old friends, and I am retired, and this year we thought it might be a good idea to sail to different places to protest about the pollution. There is a harbour fete here today, and we are distributing pamphlets.”

Vibeke appears from the boat to make a video of their plans for the day. Shortly afterwards it appears on her Facebook page. Later in the day, we see her handing out leaflets at the harbour fete.

“It’s good to see some genuine concern for the environment from a politician”, says the First Mate.

Now just what is wrong with å, ä and ö? Ha ha! but it is very annoying when you’ve written a message and then Google ‘helps’ by ‘correcting’ your hard won characters.

And I say ‘Spencer for President of the World Government’!!

LikeLike

Nothing wrong with them, now that I have found how to do them 😊. But I am still not convinced that you can’t do everything you need to do with 26 letters!

LikeLike